How to create comic book art.

Whether your goal is a job drawing superhero comics or making indie graphic novels, you need to understand how to tell a story one image at a time to become a successful comic book artist.

Where does your comic-book-drawing origin story begin?

Comic books are a narrative commercial art form. The medium covers wildly different genre and styles, from Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko’s traditional superhero cartooning to Raina Telgemeier’s autobiographical young adult story Smile to Goseki Kojima’s inked art in the manga Lone Wolf and Cub. What unifies all comic book art is that it tells a story by placing one image after another, which is why the term “sequential storytelling” is often used for the medium. Even if your goal is to do cover art for comic books, learning the storytelling tenets of good comic art is essential for building your skills to pursue a career in this competitive industry.

Basics before Batman.

“Comic books can be broken down into three different building blocks you can study,” comic book artist and instructor Phillip Sevy explains. “Human anatomy, perspective and visual storytelling.” Before you start trying to get your work in front of comics publishing powerhouses like Marvel and DC Comics, you need to hone your skills in these pillars.

Figure and life-drawing classes are a great way to improve your command of human anatomy drawing — a skill that’s important when a script may require you to illustrate people flying, falling, running or simply chatting. While comic art can feature figures with exaggerated physiques, like the classic art of Captain America co-creator Jack Kirby, nailing proportions is still essential and it’s something hiring editors will scrutinise in your work.

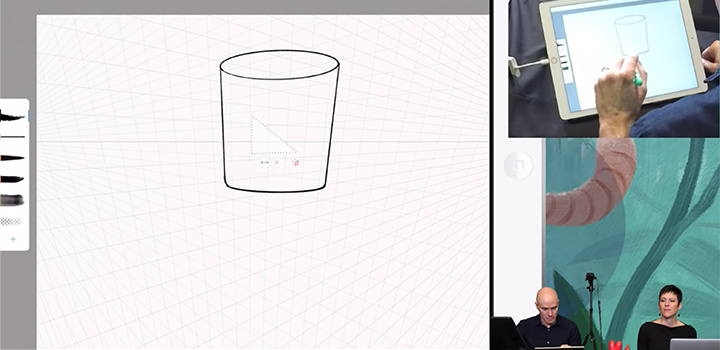

Comics artists also need to be able to draw city streets, interrogation rooms and even sci-fi space stations as the story dictates and properly place characters within those environments — and you’ll have to do it on a deadline. Drawing apps like Adobe Fresco and Adobe Photoshop Sketch have a perspective grid function that allows you to add two-point perspective or graph grids to a file as you illustrate — a great way to help you master perspective drawing. “Use reference photos and images,” artist Jen Bartel suggests. “Working in comics, artists will trace parts of backgrounds — anything that helps us to speed up the process.”

See a perspective grid in action.

Watch artist Kyle T. Webster turn on and use a perspective grid to sketch a robot.

Storytelling is of the utmost importance.

Stories progress in comic book art through a storytelling tool called “panels.” Panels are the boxes in which a moment of each scene is contained. Even the simplest three-panel comic strip shows a visual storytelling progression from the first to the last image. In animation, each illustration is used to showcase movement from second to second. The first time you sit down to draw consecutive comic panels, you’ll realise a big creative choice in comic art is how much you can have happen between two panels without confusing the audience. Readers won’t need to see two characters walk all the way from ordering food to sitting at a table to understand the progression, but characters going from Earth to the moon in two panels could be confusing.

“What makes one comic artist stand out over another is the ability to communicate a story easily.”

“What makes one comic artist stand out over another — even if an artist is a really great illustrator — is the ability to communicate a story easily,” explains former Marvel Comics editor and founder of the Comics Experience online school, Andy Schmidt. Artistic storytelling ability can be seen in the way an artist lays out panels on a page and how they draw the story beats within those different frames. Comic creators use simplistic storyboard-style art called “layouts” early in the process so the storytelling can be polished before any of the backgrounds and figures are fully rendered. With the storytelling fine-tuned in layouts, the artist then transforms sketchy art into a page of fully illustrated panels.

What art goes in each panel is an important choice. The right choices will make it clear where multiple figures are standing in relation to each other, even as the artist changes the angle by which we view them throughout a scene. Study of comics by pros like Frank Miller, Walt Simonson, Marie Severin and Stan Sakai can offer great insight into what works. And the legendary Wally Wood’s 22 Panels that Always Work is a great reference for any budding comics artist.

Breaking into the comic book industry.

With each new Avengers film setting box office records and graphic novels being adapted into TV shows by the dozen, finding a job in comics has become even more competitive. Making headway into any new field takes hard work and perseverance — it can take years to land a small job at a major publisher and possibly a decade more before you’re hired to draw an icon like Wonder Woman. Your first comic will likely be a self-published short story, but each completed page of work builds your resume. Here are a few things to consider.

1. Online presence: To get hired or connect with a creative collaborator, your work needs to be visible. Create an online portfolio that showcases your best work and demonstrates the style of comic book you want to work on. Set up social media accounts and join communities like Behance to give your work a broader platform.

2. Networking: While living in New York City gave comic book artists an edge back when DC Comics and Marvel were both headquartered there, social media, email and a growing circuit of comic book conventions offer opportunities for artists living all over. If you can’t afford to travel to make connections, digital means can be very effective, especially as many comic book artists are remote freelancers and editors and publishers make many business connections online.

3. Portfolio reviews: At certain conventions, publishers will offer portfolio reviews for artists. Before you apply for these opportunities, take your portfolio around to working artists and get feedback to improve your work. Portfolio reviews are great opportunities to receive critiques and make connections with editors, but you want to make sure you’ve ironed out any problems first. “You want to have a portfolio with several pages of sequential art — storytelling pages — that show you can tell a story,” Schmidt says. “It’s good to have the script with the page of art so the person evaluating your portfolio can make sure that you executed the story.”

4. Self-publishing: It’s recommended that artists looking to enter the field create comics to use as a resume to get more work. Seeing a complete story is the best way an editor can judge your abilities. You can create a digital comic or webcomic on your own or team up with a writer to tell a story. With crowdfunding, these efforts can even make you money. The crowdfunding revolution has led to many self-published comics anthologies, which is another avenue for you to pitch your work and get published.

Gain more insight into comics careers by learning about Gene Luen Yang and Nicola Scott’s journeys in comic book publishing.

Other art jobs in comics.

Beyond the sequential storytelling in the pages of each comic book or graphic novel, there are other artistic careers you can pursue in the medium.

- Cover artist: Comics may be the one industry that “you can’t judge a book by its cover” doesn’t apply to. Compelling art is important for a book to pop on a crowded shelf of new comics. Composition is key in these images, so study how to create compelling images with a clear focal point. “I knew that I wanted to do comic covers, so I went out of my way to create illustrations that looked like cover art,” Bartel says.

- Inker: In traditional comic book publishing, an artist known as a penciler would lay out the pages that tell the story and then hand off the work to an inker to finish the pages. Inking over the pencils of professional artists can be a great training exercise for understanding how mood and tone can be changed by the inking process.

- Colorist: Specialists in bringing vibrancy or moodiness to the page, colorists take black-and-white comic book art and add hues and tones to each page and often to cover art as well. Essential for setting the vibe of each project, a good colorist can amplify the work of a comic book artist — which is why the most talented colorists are always in demand.

- Letterer: Responsible for filling in the iconic word balloons made popular by the medium, letterers are typography and hand-drawn lettering masters that set a style for every project with the fonts they create. Letterers add sound effects to comics as well — from Wolverine’s classic “SNIKT” to every “THUD” and “THWAP.”

- Designer: Each comic book or graphic novel requires graphic design elements on the cover and interior pages, from logo placement to a stylish credits page. Comic book art has to sing and it’s book designers that make that happen.

In a medium that features art as varied as its pantheon of heroes, there’s a place for any style in comics. Working to improve your skills in anatomy, perspective and visual storytelling will help you to find where your art fits.

Contributors

Do more with Adobe Illustrator.

Create logos, icons, charts, typography, handlettering and other vector art.

You might also be interested in…

Beginning a career in children’s book illustration.

Get insight and advice into the competitive world of art for kid’s literature.

Get tips on how to draw this challenging bit of human anatomy.

How to become a professional illustrator.

Get tips on portfolio creation and art presentation to help you kick off a new career.

Get an introduction to the illustration style of Japanese comics.