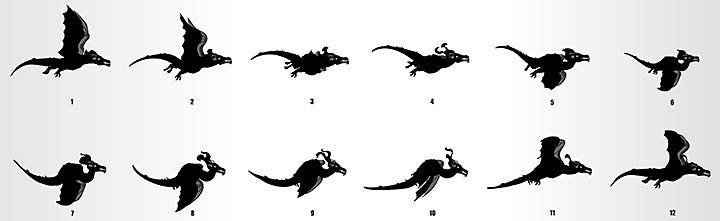

In the 17th century, magic lantern projectors presented audiences with moving figures on static backdrops. Two centuries later, Zoetrope and phenakistiscope devices created a series of quickly changing images to suggest movement for perhaps the first time.

By the early 20th century, filmmakers were taking advantage of camera technology to create animations from hand drawings and stop motion techniques. Emile Cohl’s 1908 Fantasmagorie is one of the best-known works of the era. Six years later, Earl Hurd created cel animation — the dominant animation technique for the next seven decades.

Walt Disney’s Steamboat Willie, the first outing for Mickey Mouse, was released in 1928. This was the start of a golden age of animation. The 1930s saw the launch of Disney characters from Goofy to Donald Duck, as well as Warner Bros’ Looney Tunes creations like Bugs Bunny. Within the next three decades, Disney released motion picture classics from Snow White and the Seven Dwarves to The Jungle Book. In the 1960s and 70s, countercultural animators, puppeteers and stop-motion artists brought non-mainstream techniques to a mass audience. Terry Gilliam’s anarchic sequences in Monty Python’s Flying Circus blurred the line between cutout and collage. Elsewhere in the UK, Oliver Postgate’s stop-motion creations like The Clangers charmed viewers with a gentle world of mouse-like creatures who lived on the moon, spoke in whistles and ate only soup.

Cel animation would remain prominent way into the 1980s. Here, we see the Studio Ghibli films like My Neighbour Totoro making inroads with Western audiences. But by the end of the decade, advances in computer technology led Disney to adopt digital techniques in productions like The Rescuers Down Under.

Meanwhile, Pixar’s CGI short films like Luxo Jr. were gaining traction in tandem with the rise of 3D videogaming in Japan. Pixar’s first feature film, 1995’s Toy Story, was released to critical and commercial acclaim. The CGI era had begun.