Photography

Learn about f-stop photography & what it does.

F-stops in photography measure how much light enters your lens and how bright your exposure is. Learn the ins and outs of aperture and how to pick the right f-stop setting for your shot.

Photography

F-stops in photography measure how much light enters your lens and how bright your exposure is. Learn the ins and outs of aperture and how to pick the right f-stop setting for your shot.

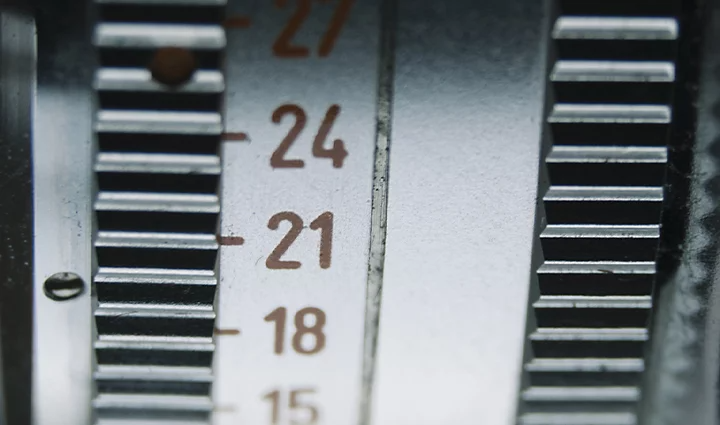

F-stop is the term used to denote aperture measurements on your camera. The aperture controls the amount of light that enters the camera lens, and it’s measured in f-stops. Along with shutter speed and ISO (sensitivity to light), aperture is the third fundamental component that makes up the exposure triangle in photography.

Not only does your f-stop setting, or f-number, help you get a proper exposure, it also helps establish the look and feel of your photo by determining the depth of field. “Unless you’re working with a whole lot of light, or in very low light, your f-stop is usually more about style and how you want the photo to look than about necessity,” says photographer Nicole Morrison.

The “f” in f-stop stands for the focal length of the lens. While focal length itself refers to the field of view of a lens, f-stop is about how much light you allow to hit the sensor via the aperture opening. The aperture is the hole in the middle of the lens, made up of rotating blades that open to let in light when you press the shutter release. The diameter of the aperture determines how much light gets through and thus how bright your exposure will be.

The range of f-stops you can shoot with is entirely dependent on your camera lens. The lowest f-stop your lens can shoot with is called the maximum aperture. Many zoom lenses have a maximum aperture of f/2.8 or f/4, and some have a variable range. A prime lens, or a lens with a fixed focal length, can handle a wider aperture because it contains fewer moving parts.

The kind of lens you should use depends on the kind of photography you do. If you need a fast, low-light lens for astrophotography, then an aperture of f/2.8 or wider is the way to go. But if you’re a landscape photographer in broad daylight, a low f-stop might not be as important. Faster lenses, those with larger apertures, tend to be more expensive, while slower lenses with smaller apertures are more budget-friendly.

The best way to maximize your budget is to know your needs so you can determine whether a wider maximum aperture is necessary for the kind of photos you take.

An f-stop is expressed as a fraction, with “f” as the numerator and the f-stop number as the denominator. The aperture size reads inversely to its corresponding f-number: The smaller the f-number, the larger the aperture. The larger the f-number, the smaller the aperture. So how do you know which aperture setting to use? Check out this guide to get familiar with common apertures used for different scenarios.

Larger apertures let in a lot of light, which makes them useful for low-light scenarios. F-stops in this range are also commonly used in portrait photography as the shallow depth of field makes subjects stand out while the background softens into a bokeh blur. “If I want someone to be in focus and everything else to fall away into the background, out of focus, I’d use a wider aperture,” says Morrison.

“If you’re interested in shallow depth of field and you’re just getting started, a great lens is a 50mm,” advises Morrison. “Almost every brand has a fairly inexpensive 50mm with a wide aperture.”

These apertures are a great mid-range for most scenarios. You’ll have a greater depth of field, so more objects will be in focus at different distances while still letting in a decent amount of light and background blur. “Another thing some people like about a smaller aperture and a wider depth of field is that you usually have more contrast,” adds Morrison.

Small apertures are good for landscapes and very well-lit scenes. At f/11 and higher, you’ll get a wide depth of field, with almost everything in your frame in focus. If you have a variety of subjects at different distances from you, dial up your aperture to ensure nothing is left out. “Product photographers also use higher f-stops because when you shoot products, it’s important for everything to be in focus,” says Morrison.

Aperture scales are handy to use as a quick reference, but they’re not the final say in how you should pick your f-stop. The truth is, there’s no single f-stop you should shoot with for any given scene. It’s a balance between your shutter speed, ISO, and aperture, and it comes down to how you want the photo to look.

If you’re shooting an indoor event with low light, you might want to stop down your aperture. But you also might not want a shallow depth of field. To keep everything in focus, you could shoot with a flash and keep your aperture in a medium range, or crank up your ISO to compensate for the low light. You could also slow down your shutter speed to let in more light.

With all of these settings, you have many options when it comes to setting up a shot. It’s a bit like solving a puzzle with different variables, and learning how to work with light takes a lot of trial and error.

Film cameras and even some digital cameras use an aperture ring on the lens itself that you rotate to set the aperture size. But most DSLRs adjust aperture via a dial or touchscreen selection. And while most film cameras can be adjusted by full stops only, most DSLR brands today allow you to choose from a wider range of increments.

“Aperture might sound confusing, but it makes a lot more sense in practice,” says Morrison. And the best way to do that is to experiment and play around. It may be tricky to balance all your settings at once, but with time it’ll get easier. Before you know it, you’ll know which conditions call for which settings like the back of your hand.