ACROBAT

How to write an academic research paper.

Learn the steps to research, write, and revise a research paper.

What is a research paper?

A research paper is a genre of academic writing that presents a new insight or perspective based on a critical collection and interpretation of empirical evidence.

Academia runs on research, so it’s no surprise that the research paper is a common assignment across college classes. It’s an excellent way to help students develop research, critical thinking, and communication skills — especially in their chosen field. It’s also the type of writing that professors do as they conduct their own research and publish papers as articles in scholarly journals.

The research involves finding, selecting, and interpreting information from primary or secondary sources. Primary sources provide original data in interviews, scientific reports, works of art, diaries, and newspaper articles. Secondary sources take a step back to add commentary and interpretation in books, magazines, scholarly articles, and editorials. Even secondary sources can serve as empirical evidence when a researcher wants to know what others have said about the subject.

A research paper usually differs from a research report. A report is a type of expository writing that simply explains a topic. A lab report, for example, explains the findings of a scientific experiment. Research papers, on the other hand, do not usually require the researcher to generate original data. Instead, the research involves gathering and organizing the data already out there, then taking it a step further by making a persuasive argument about what it all means. A research paper’s argumentative and analytical nature also sets it apart from other kinds of expository writing that simply present everything there is to know on any given topic (think of a Wikipedia page or a textbook).

Research papers can take different forms depending on the discipline, topic, and the instructor’s or publisher’s requirements. Still, writers follow a similar process to achieve the final product, even in different contexts. The writing process itself is something that some scholars spend their lives researching and writing about. Decades of academic practice have helped scholars describe and teach the best way to conduct solid research and write about it persuasively.

How to structure your research paper.

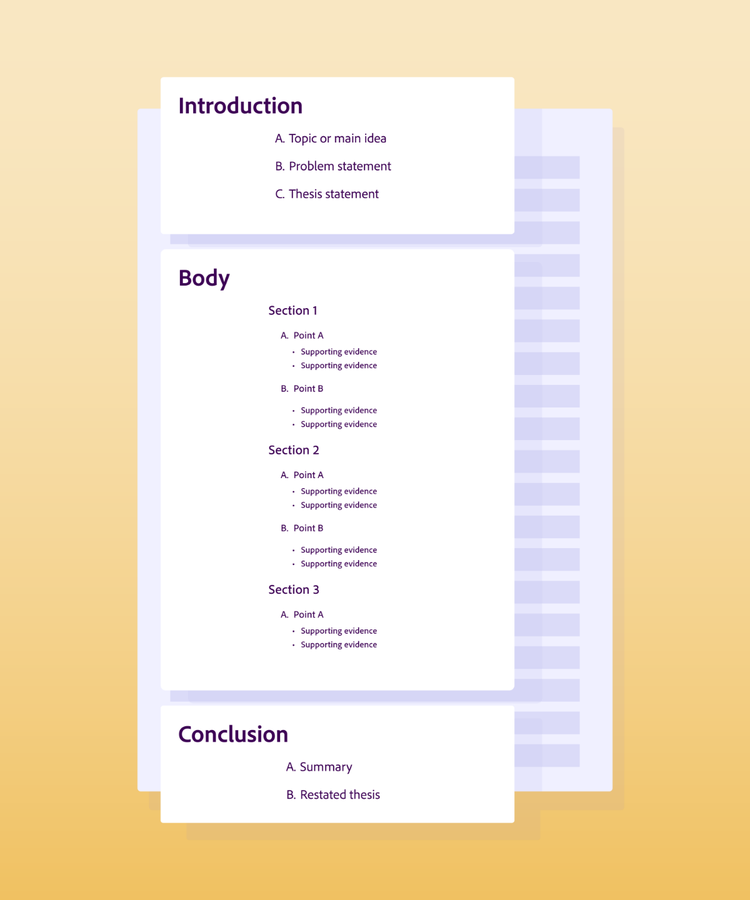

The basic elements of a research paper appear in this order:

- Title page

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Background section or literature review

- Body sections organized under subheadings

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

Although they might go by other names, most of these elements are non-negotiable. The bibliography, for example, can’t be skipped. But shorter papers might be able to present sufficient background information in the introduction so that an additional section for it isn’t necessary. For other kinds of research, you’ll need to add separate sections describing your research methods, findings, and analysis.

Find out what your instructor expects or what other writers do in the same field. Instructors can usually provide good examples of student writing, or they can help you identify the right journal articles to imitate. Imitation (not plagiarism) is a great way to learn how to write in a new genre.

Dissertation vs. thesis — what’s the difference?

Dissertations and theses are both academic research papers. The difference is that a dissertation is required to get a doctoral degree, while a thesis is often required for a master’s degree or even some undergraduate programs. A dissertation is the equivalent of a book, while a thesis is the equivalent of an article. A research paper is usually shorter, although papers can evolve into full-length articles.

How to start a research paper.

Getting started is the hardest part. But no one writes a research paper in a single day. If you plan and take it one step at a time, the project will feel slightly less overwhelming.

You might think the steps are obvious — first research, then write. But what that means is a little more complicated. You’ll do a lot of preliminary writing — taking notes, sketching ideas and outlines, or making mind maps to develop a research question and make sense of everything you’re learning. After you’ve landed on a thesis and started drafting, you’ll find that you need to do additional research to support the argument you want to make.

The basic steps to the writing process are to plan, research, and write — and then to plan, research, write, plan, research, and write again. So don’t feel discouraged if you find yourself back at the drawing board several times. You’re always building on what you’ve already learned.

Understand the assignment.

The most important first step is to understand the assignment. Many students make the mistake of not reading the assignment description carefully or not asking questions early in the process.

Find out the required page number or word count. Academic journal articles are usually 20 to 25 pages, while papers for a semester-long course are generally half as long at 10 to 12 pages. Find out the number of sources to include and whether you need to cite them or discuss them at greater length. Research papers can cite anywhere from 10 to 100 references. It depends on the topic and your approach, so understand what the instructor expects.

Find out what type of information you should be gathering. Are scholarly articles the only option, or should you consider mainly primary sources? Your instructor might require that you include particular course readings or foundational texts.

Read the rubric or any other criteria the instructor will use to evaluate the final piece to understand the standards for success and any additional requests.

Don’t be intimidated or think you have nothing to offer. You can offer a new perspective and an important contribution even as a student.

Finally, understand your audience. You might be doing this research just because it’s an assignment, and you don’t think anyone other than your instructor will ever read it. You do need to satisfy the instructor as a secondary audience or judge of success. But your instructor is not your primary audience. Your reason for writing needs to be a little bit bigger. Once you find a topic and begin researching, you’ll find a community of scholars already asking similar questions and chiming in on the conversation. Or you’ll discover that a whole group of people lack specific knowledge that could benefit them somehow.

Don’t be intimidated or think you have nothing to offer. You can offer a new perspective and an important contribution even as a student. If the assignment description doesn’t identify an audience for you, start asking yourself questions about the people in the real world who would want to read the kind of writing you’re about to do.

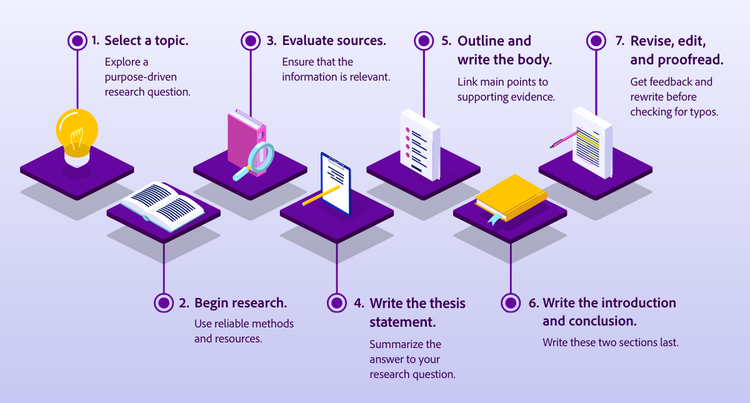

7 steps to writing an academic research paper.

Now that you know what a research paper is and what to expect from your research and writing process, you can break it down even more into manageable chunks or steps that you can follow in a linear order.

1. Select a topic.

Some students make the mistake of thinking they can select a topic and then just write everything they can find about it or that they should look for evidence that supports an opinion they already have. But the process has to start with more tentative exploration.

Selecting a topic is more like choosing a city to visit, finding a research question is like picking a restaurant, and writing a thesis statement is like ordering a menu item. The point is to start broad — but not too broad — then narrow in.

Start by thinking about general topics you’re interested in. If you don’t already know what people are saying about it, find out. For example, maybe you like young adult literature. You just like the books and you’re not aware of any controversy, so you do some internet browsing and discover how the genre has evolved in just the last few decades. You wonder what factors have influenced its growth, who is really reading it, and what determines whether a book gets published. These questions are each excellent starting points to begin conducting your research. Some questions might lead to a dead end, and some will turn up more information than you can handle, so you adjust accordingly.

If you feel like you’re just inventing something to write about, you’re in good company. This writing stage was called invention in the ancient world by thinkers like Aristotle, who outlined questions to ask about a topic. (He called these topoi — places you can find things.)

How is it defined? Who defines it?

What are its parts, or what is it a part of?

What came before, and what will come after?

How has it changed, or how will it change?

How is it similar or different from something else?

What makes it possible or impossible?

Who are the experts on this topic?

Who disagrees or misunderstands this topic?

Who has firsthand experience?

What are other people saying about it?

What rules or laws impact this topic?

2. Begin research.

In the internet age, there’s endless information out there. When you begin, you might be overwhelmed by the information available on any given topic. That’s why the most crucial research skills include asking the right questions, knowing where to find answers, and interpreting the information legitimately and persuasively.

You’re going to do a lot of reading at this stage. While research papers rarely cite tertiary sources like encyclopedias, reports, and literature reviews, these are helpful resources for quickly getting familiar with a topic. As you begin to narrow, read the bibliographies of the sources that seem most relevant and notice the names and titles everyone is referencing.

University librarians are usually delighted to help students and often know more than instructors about finding what you’re looking for.

You can find some articles on Google Scholar, but you can find more by navigating your library’s online database. Academic institutions pay for access to journals and databases unavailable on the internet. These sources are often more credible and helpful — because peer review isn’t free. Physical and digital library archives also offer precious source material.

For many students, the most underestimated and underused resource is a librarian. University librarians are usually delighted to help students and often know more than instructors about finding what you’re looking for. If you can’t get to your library in person, search the website for a librarian’s phone number and email address who specializes in your discipline.

3. Evaluate sources.

Many students make the mistake of grabbing the first 10 sources that are vaguely relevant or, conversely, getting bogged down in endless research because they feel like they have to read dozens of articles and even books from start to finish before they can form an opinion. You can avoid these mistakes by learning how to evaluate sources quickly.

While most of what you find in library search results is likely credible, it might not be relevant to your question. Take basic steps to ensure that a source is credible such as looking up the author and publication. Then determine if a source is relevant to your question by assessing its publication date, likely audience, and purpose. Read the title and abstract carefully. If it seems promising, you can read the introduction and section headings or jump straight to the conclusion. Now you should know whether it will help answer your research question or provide evidence for your argument.

Once you’ve collected the sources you want to use, read them thoroughly and take careful notes. Keep track of the page numbers where you found important information, and as you jot down notes, distinguish carefully between source material and your ideas. You’ll be grateful later on when you start writing, trying to find critical information while avoiding plagiarism. Some researchers write source notes in the left column and their thoughts on the right. Another method is to save the article as a PDF and then edit the PDF with highlights and comments you can refer to later.

4. Write the thesis statement.

You’ve done your research and learned something new that no one has been able to see from quite the same perspective. Your thesis statement should state this discovery as an argument and summarize the evidence that supports it in one sentence.

A thesis statement should be debatable or contentious, meaning that not everyone will immediately agree with it or that it requires evidence to prove. It’s not a generalized statement about the complexity or value of a topic. Instead, it takes a clear and specific position.

A thesis statement needs to make an argument, but that doesn’t mean it needs to be controversial or emotional. It just needs to offer an interpretation and take a clear stance. It also needs to be coherent with the rest of the paper, meaning each section and each paragraph should support this statement.

5. Outline and write the body.

Some students make the mistake of jumping right into the first few pages with their most robust evidence before trailing off with weak sources and weaker analysis before finally filling in the last few pages with fluff and submitting the paper just before the deadline. Avoid these perils by outlining. You’ll discover where your ideas are best, where you need to swap out weak sources, and how the whole thing can be structured more clearly if you take the time to map it out and check that each section helps prove your thesis.

The outline can include section headings, topic sentences, bullet points summarizing sources, bullet points analyzing sources, and transition sentences.

6. Write the introduction and conclusion.

It can be challenging to write a good intro until you finish — when you’ve put so much thought into it that it’s easy to summarize.

The introduction should start by explaining your research question. Zoom out to give your readers context, but not too far. Openers like “Since the birth of civilization…” or “Everyone knows…” are common mistakes. You don’t have to make your topic relevant to every human on Earth, just the ones likely already interested. Summarize what they probably already know in just a sentence or two before explaining why your research question needs to be asked and answered. The intro can be more than one paragraph, but the thesis should be the last sentence. Be sure it’s clear to your reader what the point is and what they can expect from reading the entire paper.

It’s tempting to hurry through the conclusion or even forget about it. You might think the piece speaks for itself, and it’s not necessary to restate what you’ve already stated throughout. However, the conclusion that seems obvious to you as a writer might not be apparent to your reader. Plus, as you saw in your research process, many readers want to understand the conclusion of your research even if they don’t have time to read the entire thing. Don’t offer new information. Restate the thesis, summarize everything you have presented, take a clear stance on the topic, and provide a final insight or suggestions for further research.

7. Revise, edit, and proofread.

This three-part step is a crucial part of the writing process. It starts at the global level. Once you have a complete draft, you’ll discover weaknesses in your argument and research that might require a total rewrite of some sections. Ask for feedback from your instructor, peers, or other advisors to ensure they can follow your argument, and then be willing to make significant changes.

Once you’re confident that the content is solid, you can edit the paper at a sentence level. Rephrase to improve clarity and concision. You might need to reorganize and rewrite transitions so the paper flows logically. The last step is to review it again for a final proofread where you’ll need to catch any typos and grammatical or punctuation errors.

How to cite sources for a research paper to avoid plagiarism.

Citing sources involves more than following style guide conventions for your bibliography, although that’s important too.

Understanding proper citation practices before researching can help you avoid plagiarism. Keep careful track while researching and drafting to give complete and accurate credit to all your sources. Cite page numbers not only for direct quotations but also for ideas that you paraphrase. Don’t expect to add page numbers as a final step. You won’t remember.

Instructors care about formatting — a lot. When you present your work correctly, they get the message that you’ve put thought into the assignment.

Pay attention to citation practices in academic journals and be just as thorough. For example, a sentence like “Many experts agree…” deserves an in-text citation of those experts and page numbers where you discovered this info. In-text citations can include multiple authors’ names and page numbers at the end of one sentence.

Don’t drop direct quotes randomly without explaining where they came from. Describe the author or source briefly so the reader knows why the quote is relevant.

If you use direct quotes, use them sparingly. A paper that consists almost entirely of quotations and paraphrases doesn’t present original ideas, even when cited correctly. Instead, it is a reappropriation of others’ work. Avoid plagiarism by using direct quotes only when there is no other way to present the information and by giving preference to short phrases or single sentences rather than larger chunks of text. And of course, by dedicating at least as much space to your analysis.

Getting the formatting right in your bibliography can be a pain and feel like busywork to new students. But different styles have particular rules for a reason. Getting the punctuation and formatting right can make the difference between someone being able to find and access the information you cited or not. Incomplete, incorrect citations amount to plagiarism because they can stand in the way of attribution. For example, primary authors, journal versus article titles, and the issue versus volume number can be misconstrued if you don’t take the time to use italics, quotation marks, accepted abbreviations, and the correct order.

Tools for academic research paper writing.

Use the many available tools and resources to make writing and research easier. Use a tool like Grammarly or Hemingway Editor to improve the clarity and style of your writing. Ask for feedback from peers, professors, and other trusted advisors by converting your Word file to a PDF they can mark up and comment on. The most successful writers seek feedback and revise. Go straight to style guide websites for answers to questions about formatting, or find answers to common questions on college writing center websites like Purdue OWL. You can even use AI prompts with Acrobat AI Assistant to help pull statistics out of lengthy documents, or analyze research from your sources.

Should I use MLA or APA format?

Most research papers follow the Modern Language Association (MLA) or American Psychological Association (APA) style guidelines. MLA is more common in the humanities, while APA is more common in education and science. Times New Roman, double-spaced, and 12-point font are standard. Avoid sans-serif fonts like Arial. Pay attention to the margin size, paragraph spacing, and block quotes. Some style guides offer specific instructions for how to treat first-, second-, and third-level headings — which you’ll need to distinguish sections and subsections. Add automatic page numbering.

Finally, be sure your final draft meets all the instructor’s requirements and that you submit it in a final, polished, accessible format.

Instructors care about formatting — a lot. When you present your work correctly, they get the message that you’ve put thought into the assignment. They will take your ideas more seriously. Most students today submit papers electronically instead of printing them. Avoid submitting your work as a Google Doc, Apple Notes file, or another format your instructor can’t access. Many instructors prefer or even require that students convert their files to PDFs because it ensures that formatting is locked in and viewable on any device.

Learn what more you can do with PDFs and explore the Adobe Acrobat tools that can help you draft and share your work.